About & News

HAROLD AND GLADYS PAGE

This page was published for the 75th anniversary of Victory in Japan Day, (15th August 2020). This is powerful story about my Great Grandparents that has been carefully researched by my mother Judy Barradell-Smith.

Kuala Lumpur: 1936 - 1940

My Great Grandfather, Harold James Page, who was born in 29th May 1890, was a veteran of the First World War, where he had been injured badly at Mametz Wood in 1916 while serving with the Royal Field Artillery. He and his wife Gladys Isabel Page nee Shepperd (born on the 17th September 1892) were living in Kuala Lumpur in 1936.

Harold had been appointed as the Director of the Kuala Lumpur Rubber Research Institute (RRI) in 1936 with its headquarters located in the 'Federated Malay States'. They had three children (Mike, Barbara and Denis) who had been studying in England. During summer holidays they would travel the long distance, overseas, to be together. The family home was a two storey house with lovely grounds located at 200, Ampang Rd, Kuala Lumpur.

From left to right: Gladys, J.W Page (Harold's father), Barbara (their daughter), Harold

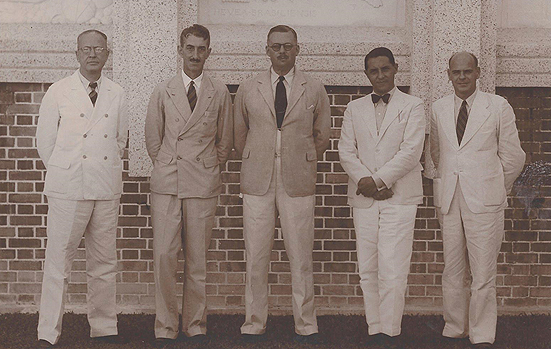

The Rubber Research Institute. Harold 3rd from left.

Escaping from Kuala Lumpur: 1941/2

As the Second World War began to take its toll in Europe, in the far East, the Japanese had launched their first air raid over Kuala Lumpur on the 21st and 22nd of December 1941. British anti-aircraft guns and RAF aircraft intercepted the attacks. More raids followed on the 25th and 27th of December. Kuala Lumpur fell to the Japanese on the 11th January 1942. As many civilians retreated, the Japanese implemented their 'scorched earth policy' where they set fire to tin mines, rubber plantations and munitions factories. Fires continued to burn for days. In the preceding days there was a mass evacuation south to Singapore because it was felt that Singapore was strongly defended and would not fall. Harold and Gladys left their house and possessions and fled to Singapore with other employees from the RRI (Kuala Lumpur Rubber Research Institute).

Escaping from Singapore: 1942

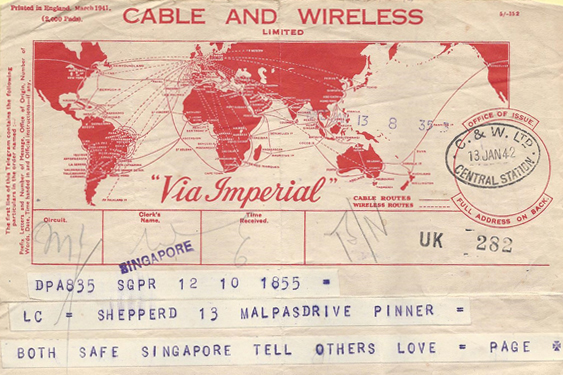

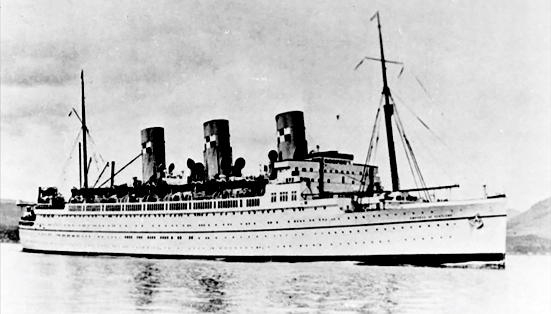

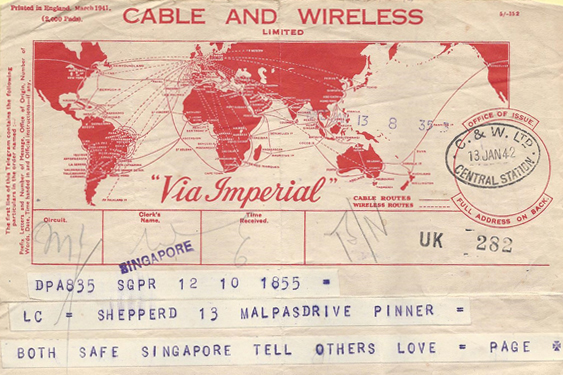

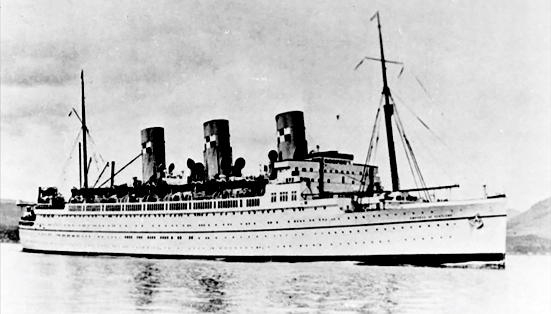

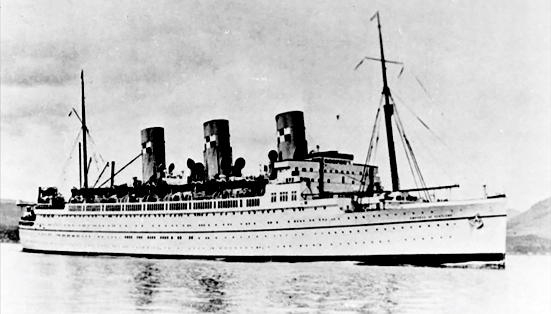

Singapore had been bombed at the end of 1941 and then with increasing frequency. The Japanese advanced steadily south, reaching the tip of the Malay Peninsular. Glady and Harold safely got to Singapore Island by the 13th of January 1942. By January 31st the Commonwealth troops were pulled back to Singapore Island. At this time there was already a lot of damage to buildings and roads and getting around was becoming more difficult by the day. As the Japanese advanced towards the city, people and vehicles were pushed towards the city centre. This included a large number of refugees including Harold and Gladys. The best route to escape the city was via the boats at the city docks. There was a 'women and children first' evacuation policy implemented. Gladys Page boarded The Empress of Japan on the 31st January 1942. Harold voluntarily elected to stay behind.

The Empress of Japan (renamed on route back to Britain as The Empress of Scotland)

The following is taken from edited extracts written by the son of two evacuees Piri and Suze Napper who were both killed/lost on the Tien Kwang that Harold was on.

The formal directive from Churchill was that people should stay at their posts in Singapore till the end, destroying facilities and supplies ahead of the Japanese advance. But on February 12th there was an official review of what small ships and boats were available for an evacuation. Instructions were sent to various military and civil organisations, telling them to select personnel who could escape and continue the war effort rather than face capture. These people had to leave without letting colleagues know what was going on, to minimise loss of morale and a stampede at the docks.

The official 'evacuation' flotilla comprised of over 40 vessels. The personnel selected were mostly military, but there were 300 passes for key civilians, e.g. Fire Service, and Public Works Department (75 passes), and a large party of nurses. There was also a considerable number of women and children left. These probably included many of those who had spurned the earlier opportunities to leave and insisted on staying with their husbands. On February 13th the officials gave out passes and notified personnel to get to the docks, with minimal hand luggage, find their allocated boat and board it.

Three employees of the RRI, Harold, Mr. Sharp and Mr. Owen had passes and were allocated to HMS Tien Kwang which was a British Royal Navy auxiliary anti-submarine vessel. It had a capacity of

between 300 - 400 passengers. The other, larger boat was the HMS Kuala which could take up to 500 passengers. This vessel only accepted women and children.

The Fall of Singapore happened on February 15th.

On Friday 13th February these two ships set sail together and were guided through the minefield outside the harbour. The Tien Kwang following the Kuala. They had instructions to sail to Batavia, Java via the straits of Rhio and Banka which was the same route earlier ships had taken. However by now the Japanese had control of the Banka straits, over 200 miles away. Many of the people escaping by boat in the days before were killed or captured in this area.

The immediate plan for the two ships was to travel by night and at daybreak seek shelter as close as possible to such an island. They would camouflage the ships with foliage from the jungle and hope they would be undetected by enemy planes until they could resume their journey at night. The first morning they reached the small island of Pompong around 50 miles away. They anchored 200 - 300 yards from the shore, and a similar distance apart, with the Tien Kwang the closer to the shore. At daybreak the ships despatched boats to gather foliage from the island to decorate the ships. Pompong was a small uninhabited island, covered in jungle, with the sides rising steeply from the water, except for a small beach on either side.

The Bombing of the Tien Kwang and Kuala

Extracted from an eye- witness account by Gwilym Owen and edited by Anna Dillon.

On the morning of February 14th, both ships were anchored close together. On board the HMS Kuala were women and children together with some men with a total number of passengers and crew estimated at about 500. Mrs Napper was a passenger on this ship. On board the HMS Tien Kwang were men only consisting of members of the armed forces and civilians with a total number estimated to be about 300. Mr Napper and the writer were passengers on this ship, along with Harold Page.

Copyright of image with grateful thanks from www.wrecksite.eu

The Japanese bombers came over and dropped a salvo of bombs. The Kuala received a direct hit and was set on fire immediately which killed many people on board. Hundreds of people jumped over the side of the ship. Orders were given to abandon ship. I did not go overboard as I realised I could never reach the island. I can't swim and I did not have a lifebelt. I remember looking over the side after a short interval and seeing Messrs Napper, Page and Sharp amongst hundreds of others swimming towards the island. Just at that moment the Japanese bombers came over again and I rushed down to the bowels of the ship. The Tien Kwang was hit but apparently no serious damage was done, at least the ship was not sinking. I shall not attempt to describe what I saw when I came to the side of the ship again but suffice it to say that it was evident that most of the bombs dropped by the Japanese bombers when they came over a second time must have fallen in the water between the ship and the island and the result can be imagined. Those who were still swimming were too far away to be recognised and I did not see Napper, Page or Sharp.

I jumped overboard when a raft was dropped into the water from the top deck. I clung to this (along with others) and we were carried away by a very strong current which flowed parallel with the island and despite our efforts we failed to reach this particular island. (We were picked up by locals in a rowing boat about 8 hours later. The planes came over a third time and more bombs were dropped. I got the impression then, as did many others, that the enemy machine-gunned the people in the water but there seems to be some doubt about this. When the immediate danger was over I looked back and saw that the Tien Kwang was still afloat but there was no sign of the Kuala.

It is clear from the foregoing that I cannot state definitely at what precise moment Mr and Mrs Napper lost their lives. It is known that neither reached the island near which the ships were anchored (Mr Page can vouch for this) and it is unlikely that they reached any of the other islands in the archipelago as it is believed that all those who did succeed in reaching any of the numerous islands were accounted for later.

END OF ACCOUNT BY MR OWEN

Further reading on HMS Kuala can be read here:

https://www.navyhistory.org.au/the-loss-of-hms-kuala-1942/

In the end around 600 people made it to the island. Of the rest, say 300, some were killed outright by the three direct hits on the Kuala, some drowned swimming for the shore, many were killed by the subsequent bombing attacks on the people in the water, and some were swept away from the island by the strong current, to be picked up in time. As well as rafts, all movable floating material was torn from the ships before they were abandoned and thrown into the water.

The survivors on Pompong, including Harold, were taken off by various boats of different types over the following week. The first batch of 200 women, children and badly injured were taken on board the small Dutch Steamer Tandong Pinang which was bound for Batavia but then got captured by the Japanese. Most of the others, and those swept away but picked up like Mr. Owen, managed to get to the mouth of the Indragiri river. But the majority failed to get a ship out in time to Batavia or Columbo, and were taken prisoner when the Japanese arrived in early March.

Gladys Page arrived back in Liverpool on the 19th March.

Capture by the Japanese

It appears from the various accounts that a number of those escaping Pompong Island, did succeed in making their way across land to Sumatra and the capital, Pedang, in the hope they could get away from there. Indeed, some did escape but not Harold. He was one of many captured when Padang was overrun by the Japanese on St Patricks Day (17th March 1942). The conditions in these camps were very harsh and food was scarce but despite this it was not nearly as bad as in other places as it had never been intended to be a Prisoner of War camp. There is anecdotal evidence that civilian captives were treated a little bit better than the military personal. However, for most there was only one meagre cup of rice fed to them per day. There were many deaths from disease and malnutrition.

Both the British Authorities, the Red Cross and the Japanese referred to civilian captives as internees, whilst combatants serving in the forces, irrespective of their nationality were always called

Prisoners of War (POW’s) Harold PAGE was a civilian internee.

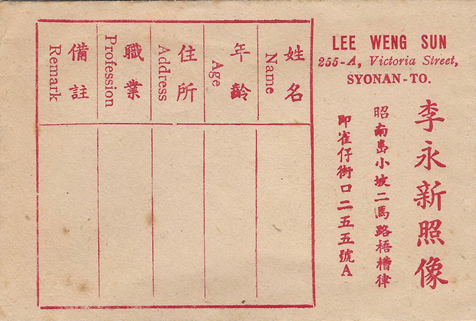

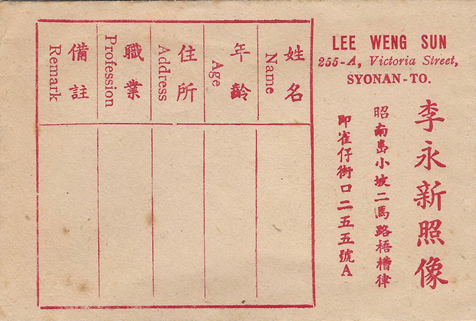

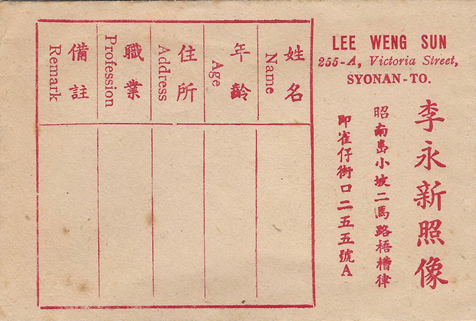

Harold's Civilian Internee ID card

In October 1943 European men and boys including Harold, who had been interned in the camp at Padang, were brought to a newly built men’s 'prison camp' near Bangkinang which is around 70km West of Pakan Baroe on the way to Bukittinggi. On this site there was a rubber factory. The women and children followed in December 1943 where they were housed in newly built sheds around 3km west of the rubber factory. By the end of 1944 there were nearly 3.200 civilians interned in these two camps. In 1945 alone approximately 140 persons died from disease and exhaustion.

Bangkinang Camp

August 15th is the day that Europe commemorate VJ Day (Victory in Japan). For Harold, he was to learn of the Japanese surrender when it was announced on August 22nd. Internees were gradually shipped out in the weeks following that surrender. Family stories say that Harold weighed around 6 stone (85 pounds) on his release.

It is highly likely that he would have been unware of the bombing of Pearl Harbour or the terrible devastation that the two atom bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused until he had been released from the camp.

Harold was finally evacuated on board The Highland Monarch which started out from Hong Kong and stopped off in Singapore where he boarded. He arrived in Southampton on the 9th November 1945.

On his return to England, he was to learn of the tragic death of his youngest son, Denis Page, who had died at the age of 20 when his Mustang III crashed in Kent.

After the war

Despite their experiences, Gladys and Harold decided to return to live in Malaya after the war. They returned to their original house in Ampang Rd, Kuala Lumpur and discovered the kindness of their neighbours and past employees who had taken their precious and personal items from their home and hidden them from the occupying Japanese.

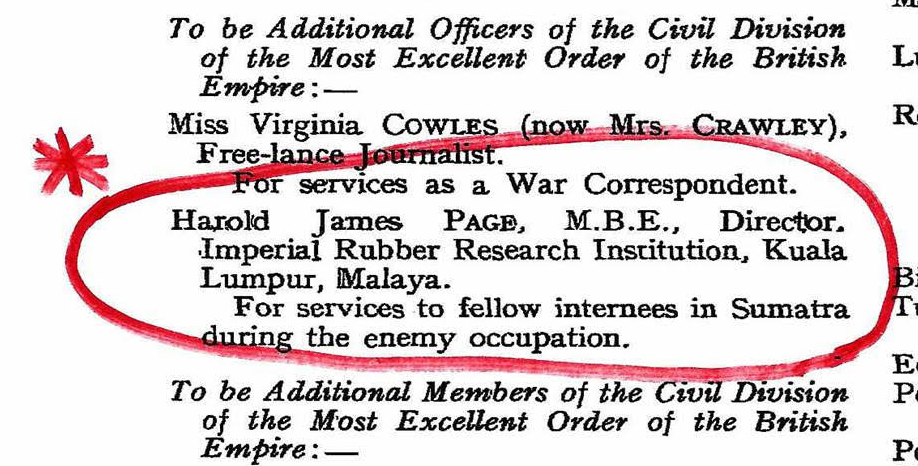

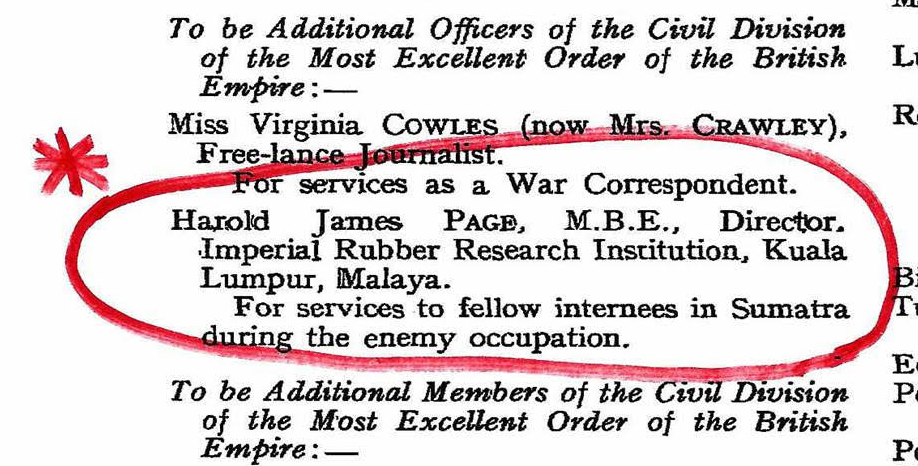

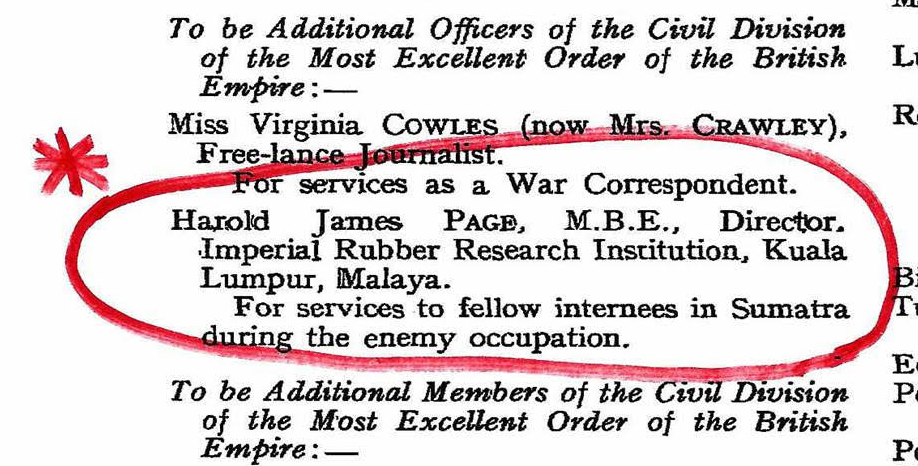

In July 1947, Harold Page was awarded an MBE “for service to fellow internees in Sumatra during enemy occupation” AND The British Empire Medal “for brave conduct under enemy fire”

The London Gazette - June 1947

Harold is remembered by his grandchildren as a happy, laughing, kindly man who loved life, loved his family, music, watching TV, enjoying the theatre, reading, travelling, gardening, watching polo and looking after his two black poodles. His grandchildren all remember him from their stays where he read Rupert Bear stories to them. According to his son Mike, because of his treatment by the Japanese and the dreadful things he had seen, he refused to meet up with anyone from Japan unless there was no other choice (work related for example). He never knowingly bought, ate or used anything that came from Japan. He remained mostly silent about his time as a P.O.W.

Gladys was a wonderfully warm lady. She enjoyed living abroad which included Italy and for a time after the war, in Trinidad. Gladys loved baking, cooking and dining out. She was an accomplished gardener and grew amazing flowers. She adored her dogs and watching polo. Gladys was very kind and when she became a grandparent she would take her grandchildren out for long walks. She would have interesting things in her house for them to look at, such as piles of coloured magazines or dozens of pipe cleaners and she would create 'stick people' and then weave magical stories around them. She and Harold were very close and happy together. She was always smiling.

1948. Gladys, son Mike and Harold on a family trip to France in 1948

Escaping from Singapore: 1942

Singapore had been bombed at the end of 1941 and then with increasing frequency. The Japanese advanced steadily south, reaching the tip of the Malay Peninsular. Glady and Harold safely got to Singapore Island by the 13th of January 1942. By January 31st the Commonwealth troops were pulled back to Singapore Island. At this time there was already a lot of damage to buildings and roads and getting around was becoming more difficult by the day. As the Japanese advanced towards the city, people and vehicles were pushed towards the city centre. This included a large number of refugees including Harold and Gladys. The best route to escape the city was via the boats at the city docks. There was a 'women and children first' evacuation policy implemented. Gladys Page boarded The Empress of Japan on the 31st January 1942. Harold voluntarily elected to stay behind.

The Empress of Japan (renamed on route back to Britain as The Empress of Scotland)

The following is taken from edited extracts written by the son of two evacuees Piri and Suze Napper who were both killed/lost on the Tien Kwang that Harold was on.

The formal directive from Churchill was that people should stay at their posts in Singapore till the end, destroying facilities and supplies ahead of the Japanese advance. But on February 12th there was an official review of what small ships and boats were available for an evacuation. Instructions were sent to various military and civil organisations, telling them to select personnel who could escape and continue the war effort rather than face capture. These people had to leave without letting colleagues know what was going on, to minimise loss of morale and a stampede at the docks.

The official 'evacuation' flotilla comprised of over 40 vessels. The personnel selected were mostly military, but there were 300 passes for key civilians, e.g. Fire Service, and Public Works Department (75 passes), and a large party of nurses. There was also a considerable number of women and children left. These probably included many of those who had spurned the earlier opportunities to leave and insisted on staying with their husbands. On February 13th the officials gave out passes and notified personnel to get to the docks, with minimal hand luggage, find their allocated boat and board it.

Three employees of the RRI, Harold, Mr. Sharp and Mr. Owen had passes and were allocated to HMS Tien Kwang which was a British Royal Navy auxiliary anti-submarine vessel. It had a capacity of

between 300 - 400 passengers. The other, larger boat was the HMS Kuala which could take up to 500 passengers. This vessel only accepted women and children.

The Fall of Singapore happened on February 15th.

On Friday 13th February these two ships set sail together and were guided through the minefield outside the harbour. The Tien Kwang following the Kuala. They had instructions to sail to Batavia, Java via the straits of Rhio and Banka which was the same route earlier ships had taken. However by now the Japanese had control of the Banka straits, over 200 miles away. Many of the people escaping by boat in the days before were killed or captured in this area.

The immediate plan for the two ships was to travel by night and at daybreak seek shelter as close as possible to such an island. They would camouflage the ships with foliage from the jungle and hope they would be undetected by enemy planes until they could resume their journey at night. The first morning they reached the small island of Pompong around 50 miles away. They anchored 200 - 300 yards from the shore, and a similar distance apart, with the Tien Kwang the closer to the shore. At daybreak the ships despatched boats to gather foliage from the island to decorate the ships. Pompong was a small uninhabited island, covered in jungle, with the sides rising steeply from the water, except for a small beach on either side.

The Bombing of the Tien Kwang and Kuala

Extracted from an eye- witness account by Gwilym Owen and edited by Anna Dillon.

On the morning of February 14th, both ships were anchored close together. On board the HMS Kuala were women and children together with some men with a total number of passengers and crew estimated at about 500. Mrs Napper was a passenger on this ship. On board the HMS Tien Kwang were men only consisting of members of the armed forces and civilians with a total number estimated to be about 300. Mr Napper and the writer were passengers on this ship, along with Harold Page.

Copyright of image with grateful thanks from www.wrecksite.eu

The Japanese bombers came over and dropped a salvo of bombs. The Kuala received a direct hit and was set on fire immediately which killed many people on board. Hundreds of people jumped over the side of the ship. Orders were given to abandon ship. I did not go overboard as I realised I could never reach the island. I can't swim and I did not have a lifebelt. I remember looking over the side after a short interval and seeing Messrs Napper, Page and Sharp amongst hundreds of others swimming towards the island. Just at that moment the Japanese bombers came over again and I rushed down to the bowels of the ship. The Tien Kwang was hit but apparently no serious damage was done, at least the ship was not sinking. I shall not attempt to describe what I saw when I came to the side of the ship again but suffice it to say that it was evident that most of the bombs dropped by the Japanese bombers when they came over a second time must have fallen in the water between the ship and the island and the result can be imagined. Those who were still swimming were too far away to be recognised and I did not see Napper, Page or Sharp.

I jumped overboard when a raft was dropped into the water from the top deck. I clung to this (along with others) and we were carried away by a very strong current which flowed parallel with the island and despite our efforts we failed to reach this particular island. (We were picked up by locals in a rowing boat about 8 hours later. The planes came over a third time and more bombs were dropped. I got the impression then, as did many others, that the enemy machine-gunned the people in the water but there seems to be some doubt about this. When the immediate danger was over I looked back and saw that the Tien Kwang was still afloat but there was no sign of the Kuala.

It is clear from the foregoing that I cannot state definitely at what precise moment Mr and Mrs Napper lost their lives. It is known that neither reached the island near which the ships were anchored (Mr Page can vouch for this) and it is unlikely that they reached any of the other islands in the archipelago as it is believed that all those who did succeed in reaching any of the numerous islands were accounted for later.

END OF ACCOUNT BY MR OWEN

Further reading on HMS Kuala can be read here:

https://www.navyhistory.org.au/the-loss-of-hms-kuala-1942/

In the end around 600 people made it to the island. Of the rest, say 300, some were killed outright by the three direct hits on the Kuala, some drowned swimming for the shore, many were killed by the subsequent bombing attacks on the people in the water, and some were swept away from the island by the strong current, to be picked up in time. As well as rafts, all movable floating material was torn from the ships before they were abandoned and thrown into the water.

The survivors on Pompong, including Harold, were taken off by various boats of different types over the following week. The first batch of 200 women, children and badly injured were taken on board the small Dutch Steamer Tandong Pinang which was bound for Batavia but then got captured by the Japanese. Most of the others, and those swept away but picked up like Mr. Owen, managed to get to the mouth of the Indragiri river. But the majority failed to get a ship out in time to Batavia or Columbo, and were taken prisoner when the Japanese arrived in early March.

Gladys Page arrived back in Liverpool on the 19th March.

Capture by the Japanese

It appears from the various accounts that a number of those escaping Pompong Island, did succeed in making their way across land to Sumatra and the capital, Pedang, in the hope they could get away from there. Indeed, some did escape but not Harold. He was one of many captured when Padang was overrun by the Japanese on St Patricks Day (17th March 1942). The conditions in these camps were very harsh and food was scarce but despite this it was not nearly as bad as in other places as it had never been intended to be a Prisoner of War camp. There is anecdotal evidence that civilian captives were treated a little bit better than the military personal. However, for most there was only one meagre cup of rice fed to them per day. There were many deaths from disease and malnutrition.

Both the British Authorities, the Red Cross and the Japanese referred to civilian captives as internees, whilst combatants serving in the forces, irrespective of their nationality were always called

Prisoners of War (POW’s) Harold PAGE was a civilian internee.

Harold's Civilian Internee ID card

In October 1943 European men and boys including Harold, who had been interned in the camp at Padang, were brought to a newly built men’s 'prison camp' near Bangkinang which is around 70km West of Pakan Baroe on the way to Bukittinggi. On this site there was a rubber factory. The women and children followed in December 1943 where they were housed in newly built sheds around 3km west of the rubber factory. By the end of 1944 there were nearly 3.200 civilians interned in these two camps. In 1945 alone approximately 140 persons died from disease and exhaustion.

Bangkinang Camp

August 15th is the day that Europe commemorate VJ Day (Victory in Japan). For Harold, he was to learn of the Japanese surrender when it was announced on August 22nd. Internees were gradually shipped out in the weeks following that surrender. Family stories say that Harold weighed around 6 stone (85 pounds) on his release.

It is highly likely that he would have been unware of the bombing of Pearl Harbour or the terrible devastation that the two atom bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused until he had been released from the camp.

Harold was finally evacuated on board The Highland Monarch which started out from Hong Kong and stopped off in Singapore where he boarded. He arrived in Southampton on the 9th November 1945.

On his return to England, he was to learn of the tragic death of his youngest son, Denis Page, who had died at the age of 20 when his Mustang III crashed in Kent.

After the war

Despite their experiences, Gladys and Harold decided to return to live in Malaya after the war. They returned to their original house in Ampang Rd, Kuala Lumpur and discovered the kindness of their neighbours and past employees who had taken their precious and personal items from their home and hidden them from the occupying Japanese.

In July 1947, Harold Page was awarded an MBE “for service to fellow internees in Sumatra during enemy occupation” AND The British Empire Medal “for brave conduct under enemy fire”

The London Gazette - June 1947

Harold is remembered by his grandchildren as a happy, laughing, kindly man who loved life, loved his family, music, watching TV, enjoying the theatre, reading, travelling, gardening, watching polo and looking after his two black poodles. His grandchildren all remember him from their stays where he read Rupert Bear stories to them. According to his son Mike, because of his treatment by the Japanese and the dreadful things he had seen, he refused to meet up with anyone from Japan unless there was no other choice (work related for example). He never knowingly bought, ate or used anything that came from Japan. He remained mostly silent about his time as a P.O.W.

Gladys was a wonderfully warm lady. She enjoyed living abroad which included Italy and for a time after the war, in Trinidad. Gladys loved baking, cooking and dining out. She was an accomplished gardener and grew amazing flowers. She adored her dogs and watching polo. Gladys was very kind and when she became a grandparent she would take her grandchildren out for long walks. She would have interesting things in her house for them to look at, such as piles of coloured magazines or dozens of pipe cleaners and she would create 'stick people' and then weave magical stories around them. She and Harold were very close and happy together. She was always smiling.

1948. Gladys, son Mike and Harold on a family trip to France in 1948

The Empress of Japan (renamed on route back to Britain as The Empress of Scotland)

The formal directive from Churchill was that people should stay at their posts in Singapore till the end, destroying facilities and supplies ahead of the Japanese advance. But on February 12th there was an official review of what small ships and boats were available for an evacuation. Instructions were sent to various military and civil organisations, telling them to select personnel who could escape and continue the war effort rather than face capture. These people had to leave without letting colleagues know what was going on, to minimise loss of morale and a stampede at the docks.

The official 'evacuation' flotilla comprised of over 40 vessels. The personnel selected were mostly military, but there were 300 passes for key civilians, e.g. Fire Service, and Public Works Department (75 passes), and a large party of nurses. There was also a considerable number of women and children left. These probably included many of those who had spurned the earlier opportunities to leave and insisted on staying with their husbands. On February 13th the officials gave out passes and notified personnel to get to the docks, with minimal hand luggage, find their allocated boat and board it.

Three employees of the RRI, Harold, Mr. Sharp and Mr. Owen had passes and were allocated to HMS Tien Kwang which was a British Royal Navy auxiliary anti-submarine vessel. It had a capacity of between 300 - 400 passengers. The other, larger boat was the HMS Kuala which could take up to 500 passengers. This vessel only accepted women and children.

The Fall of Singapore happened on February 15th.

On Friday 13th February these two ships set sail together and were guided through the minefield outside the harbour. The Tien Kwang following the Kuala. They had instructions to sail to Batavia, Java via the straits of Rhio and Banka which was the same route earlier ships had taken. However by now the Japanese had control of the Banka straits, over 200 miles away. Many of the people escaping by boat in the days before were killed or captured in this area.

The immediate plan for the two ships was to travel by night and at daybreak seek shelter as close as possible to such an island. They would camouflage the ships with foliage from the jungle and hope they would be undetected by enemy planes until they could resume their journey at night. The first morning they reached the small island of Pompong around 50 miles away. They anchored 200 - 300 yards from the shore, and a similar distance apart, with the Tien Kwang the closer to the shore. At daybreak the ships despatched boats to gather foliage from the island to decorate the ships. Pompong was a small uninhabited island, covered in jungle, with the sides rising steeply from the water, except for a small beach on either side.

The Bombing of the Tien Kwang and Kuala

On the morning of February 14th, both ships were anchored close together. On board the HMS Kuala were women and children together with some men with a total number of passengers and crew estimated at about 500. Mrs Napper was a passenger on this ship. On board the HMS Tien Kwang were men only consisting of members of the armed forces and civilians with a total number estimated to be about 300. Mr Napper and the writer were passengers on this ship, along with Harold Page.

Copyright of image with grateful thanks from www.wrecksite.eu

The Japanese bombers came over and dropped a salvo of bombs. The Kuala received a direct hit and was set on fire immediately which killed many people on board. Hundreds of people jumped over the side of the ship. Orders were given to abandon ship. I did not go overboard as I realised I could never reach the island. I can't swim and I did not have a lifebelt. I remember looking over the side after a short interval and seeing Messrs Napper, Page and Sharp amongst hundreds of others swimming towards the island. Just at that moment the Japanese bombers came over again and I rushed down to the bowels of the ship. The Tien Kwang was hit but apparently no serious damage was done, at least the ship was not sinking. I shall not attempt to describe what I saw when I came to the side of the ship again but suffice it to say that it was evident that most of the bombs dropped by the Japanese bombers when they came over a second time must have fallen in the water between the ship and the island and the result can be imagined. Those who were still swimming were too far away to be recognised and I did not see Napper, Page or Sharp.

I jumped overboard when a raft was dropped into the water from the top deck. I clung to this (along with others) and we were carried away by a very strong current which flowed parallel with the island and despite our efforts we failed to reach this particular island. (We were picked up by locals in a rowing boat about 8 hours later. The planes came over a third time and more bombs were dropped. I got the impression then, as did many others, that the enemy machine-gunned the people in the water but there seems to be some doubt about this. When the immediate danger was over I looked back and saw that the Tien Kwang was still afloat but there was no sign of the Kuala.

It is clear from the foregoing that I cannot state definitely at what precise moment Mr and Mrs Napper lost their lives. It is known that neither reached the island near which the ships were anchored (Mr Page can vouch for this) and it is unlikely that they reached any of the other islands in the archipelago as it is believed that all those who did succeed in reaching any of the numerous islands were accounted for later.

END OF ACCOUNT BY MR OWEN

Further reading on HMS Kuala can be read here: https://www.navyhistory.org.au/the-loss-of-hms-kuala-1942/In the end around 600 people made it to the island. Of the rest, say 300, some were killed outright by the three direct hits on the Kuala, some drowned swimming for the shore, many were killed by the subsequent bombing attacks on the people in the water, and some were swept away from the island by the strong current, to be picked up in time. As well as rafts, all movable floating material was torn from the ships before they were abandoned and thrown into the water.

The survivors on Pompong, including Harold, were taken off by various boats of different types over the following week. The first batch of 200 women, children and badly injured were taken on board the small Dutch Steamer Tandong Pinang which was bound for Batavia but then got captured by the Japanese. Most of the others, and those swept away but picked up like Mr. Owen, managed to get to the mouth of the Indragiri river. But the majority failed to get a ship out in time to Batavia or Columbo, and were taken prisoner when the Japanese arrived in early March.

Gladys Page arrived back in Liverpool on the 19th March.

Capture by the Japanese

It appears from the various accounts that a number of those escaping Pompong Island, did succeed in making their way across land to Sumatra and the capital, Pedang, in the hope they could get away from there. Indeed, some did escape but not Harold. He was one of many captured when Padang was overrun by the Japanese on St Patricks Day (17th March 1942). The conditions in these camps were very harsh and food was scarce but despite this it was not nearly as bad as in other places as it had never been intended to be a Prisoner of War camp. There is anecdotal evidence that civilian captives were treated a little bit better than the military personal. However, for most there was only one meagre cup of rice fed to them per day. There were many deaths from disease and malnutrition.

Both the British Authorities, the Red Cross and the Japanese referred to civilian captives as internees, whilst combatants serving in the forces, irrespective of their nationality were always called Prisoners of War (POW’s) Harold PAGE was a civilian internee.

Harold's Civilian Internee ID card

In October 1943 European men and boys including Harold, who had been interned in the camp at Padang, were brought to a newly built men’s 'prison camp' near Bangkinang which is around 70km West of Pakan Baroe on the way to Bukittinggi. On this site there was a rubber factory. The women and children followed in December 1943 where they were housed in newly built sheds around 3km west of the rubber factory. By the end of 1944 there were nearly 3.200 civilians interned in these two camps. In 1945 alone approximately 140 persons died from disease and exhaustion.

Bangkinang Camp

August 15th is the day that Europe commemorate VJ Day (Victory in Japan). For Harold, he was to learn of the Japanese surrender when it was announced on August 22nd. Internees were gradually shipped out in the weeks following that surrender. Family stories say that Harold weighed around 6 stone (85 pounds) on his release.

It is highly likely that he would have been unware of the bombing of Pearl Harbour or the terrible devastation that the two atom bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused until he had been released from the camp.

Harold was finally evacuated on board The Highland Monarch which started out from Hong Kong and stopped off in Singapore where he boarded. He arrived in Southampton on the 9th November 1945.

On his return to England, he was to learn of the tragic death of his youngest son, Denis Page, who had died at the age of 20 when his Mustang III crashed in Kent.

After the war

Despite their experiences, Gladys and Harold decided to return to live in Malaya after the war. They returned to their original house in Ampang Rd, Kuala Lumpur and discovered the kindness of their neighbours and past employees who had taken their precious and personal items from their home and hidden them from the occupying Japanese.

In July 1947, Harold Page was awarded an MBE “for service to fellow internees in Sumatra during enemy occupation” AND The British Empire Medal “for brave conduct under enemy fire”

The London Gazette - June 1947

Harold is remembered by his grandchildren as a happy, laughing, kindly man who loved life, loved his family, music, watching TV, enjoying the theatre, reading, travelling, gardening, watching polo and looking after his two black poodles. His grandchildren all remember him from their stays where he read Rupert Bear stories to them. According to his son Mike, because of his treatment by the Japanese and the dreadful things he had seen, he refused to meet up with anyone from Japan unless there was no other choice (work related for example). He never knowingly bought, ate or used anything that came from Japan. He remained mostly silent about his time as a P.O.W.

Gladys was a wonderfully warm lady. She enjoyed living abroad which included Italy and for a time after the war, in Trinidad. Gladys loved baking, cooking and dining out. She was an accomplished gardener and grew amazing flowers. She adored her dogs and watching polo. Gladys was very kind and when she became a grandparent she would take her grandchildren out for long walks. She would have interesting things in her house for them to look at, such as piles of coloured magazines or dozens of pipe cleaners and she would create 'stick people' and then weave magical stories around them. She and Harold were very close and happy together. She was always smiling.